Dublin Core

Title

Description

During the mid-twentieth century, thousands of roadtrippers traveled highways that crisscrossed the American West. But travel wasn’t safe for everyone. Black tourists risked discrimination and violence on their journeys. To ease the struggle of traveling through unfriendly or segregated towns and cities, Black tourists turned to what was called the Negro Motorist Green Book. In Utah, national parks drew visitors of all backgrounds and the Green Book served as a guide for helping ensure a safe visit.

Founded by Black New York postman Victor Hugo Green in the 1930s, the Green Book listings featured hotels, restaurants, and other businesses that served Black patrons. Early editions of the Green Book contained no listings for Utah. Routes through Utah were unpopular for the casual visitor and most Black travelers likely stayed with friends or family. It wasn’t until 1940 that the JH Hotel in Salt Lake City appeared in the guidebook.

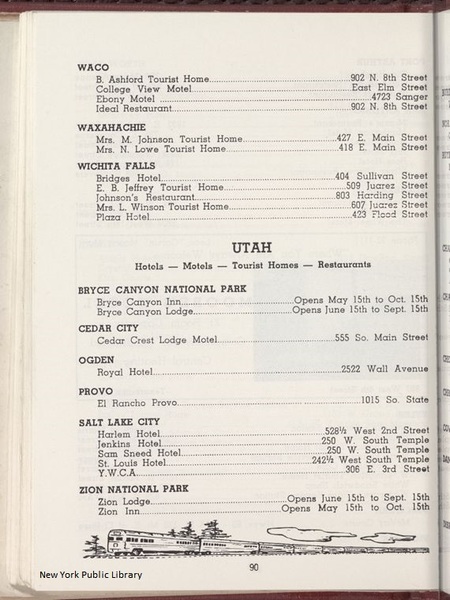

After World War II, however, more visitors than ever were driving through Utah to explore national parks and wilderness areas: including travelers using the Green Book. National Parks were subject to state and local laws, including Jim Crow segregation laws. But in 1945 the Secretary of the Interior prohibited segregation in the parks, which sparked debate over who exactly could enjoy and benefit from national lands. Visitorship to parks continued to increase and by the mid-1950s, listings in the Green Book included the Bryce Canyon Lodge, Zion Lodge, and Cedar City’s Cedar Crest Lodge Motel. Black-friendly restaurants and other businesses were still few and far between and Black travelers risked being turned away or harassed -- even if they had a place to stay.

Of course, segregation didn’t need to be written into law to make Black visitors feel unwelcome. As late as 1962, only fifteen options for food or motels in Utah were included in the Green Book. For non-Black travelers, accommodations numbered in the hundreds. Today, the National Park Service is still grappling with how to welcome more visitors of color and honor the history of those who relied on the Green Book to make their way to America’s public lands.Creator

Source

_______________

See Christine Cooper-Rompato, “Utah in the Green Book,”Utah Historical Quarterly (vol. 88, no. 1), Winter 2020; Christine Cooper-Rompato, “Researching Segregation in Utah,” Utah Historical Society; Carter Williams, “The Sobering History of the Real ‘Green Book’ in Utah and the US,” KSL, December 6, 2018; James Edward Mills, “Here’s How National Parks Are Working to Fight Racism”, National Geographic, June 23, 2020; Kurt Repanshek, “How the National Park Service Grappled with Segregation During the 20th Century,” National Parks Traveler, August 18, 2019; James Edward Mills, “These People of Color Transformed US National Parks”, National Geographic, August 5, 2020; Jamie McGriff, “Utah Professor Shows Little-Known Green Book Site Near Delta Center”, KUTV, June 2, 2023.